Josephine Sibley Couper

Despite the ravages of the American Civil War, the Sibley family of Augusta, Georgia, retained their fortune, which provided a comfortable childhood for Josephine. Her early passion for art was nurtured by a trip abroad at the age of twelve, and when she returned her father hired an instructor and equipped a studio for her use. The following year, Josephine Sibley enrolled at the Art Students League, funded by the sale of some property he had left her iupon his death.

At the League, William Merritt Chase was her mentor. In 1890, Sibley made a second grand tour of Europe, where she sketched genre scenes and copied old master paintings. The following year, she returned home and married a widower sixteen years her senior.

For women artists, marriage raised certain issues. Balancing household and childrearing responsibilities with a desire to be creative was a daily challenge. Developing a professional identity in the public arena was complicated, too. In the South, these dilemmas were aggravated by traditional, conservative values. Like her father, Couper’s husband encouraged his wife’s creativity and constructed a studio as an “integral part” of their residence, “not an addition.” During their fourteen-year marriage, Josephine Sibley Couper was a dutiful wife and mother of two children, and primarily painted likenesses of family members and friends. Over her long career, she is frequently listed in exhibition brochures as “Mrs. B. King Couper,” although she regularly—and surreptitiously—signed her work “J. S. Couper,” which did not divulge her gender.

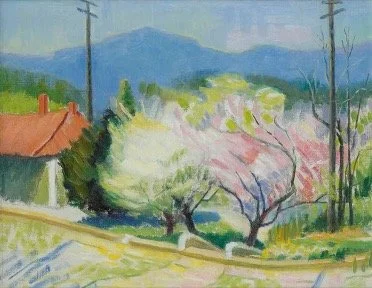

Once her children came of age, Couper broadened her subject matter as well as her style. She studied under Elliott Daingerfield in Blowing Rock, North Carolina, and spent several summers in Gloucester, Massachusetts, where her instructor was Hugh Breckinridge. From 1929 to 1930, at the age of sixty-two, Couper spent time abroad, living in Paris and taking classes under the French Cubist, André Lhote, probably at the suggestion of her distant cousin and fellow artist, Margaret Law, who had studied with him earlier. Couper attempted some abstracted paintings, but did not embrace the style wholeheartedly. Most of her career she pursued a conventional form of realism, and, by the 1920s, the influence of Impressionism became more evident.

Given her financial security, Couper never felt compelled to sell her work, even though she exhibited widely with such entities as the Southern States Art League, the National Association of Women Artists, and in Paris at the 1930 Salon d’Automne. In 1927, the High Museum of Art in Atlanta hosted a solo exhibition in her honor. When Couper happened to make a sale, she donated the proceeds, after expenses, to her church or to missions in Africa.